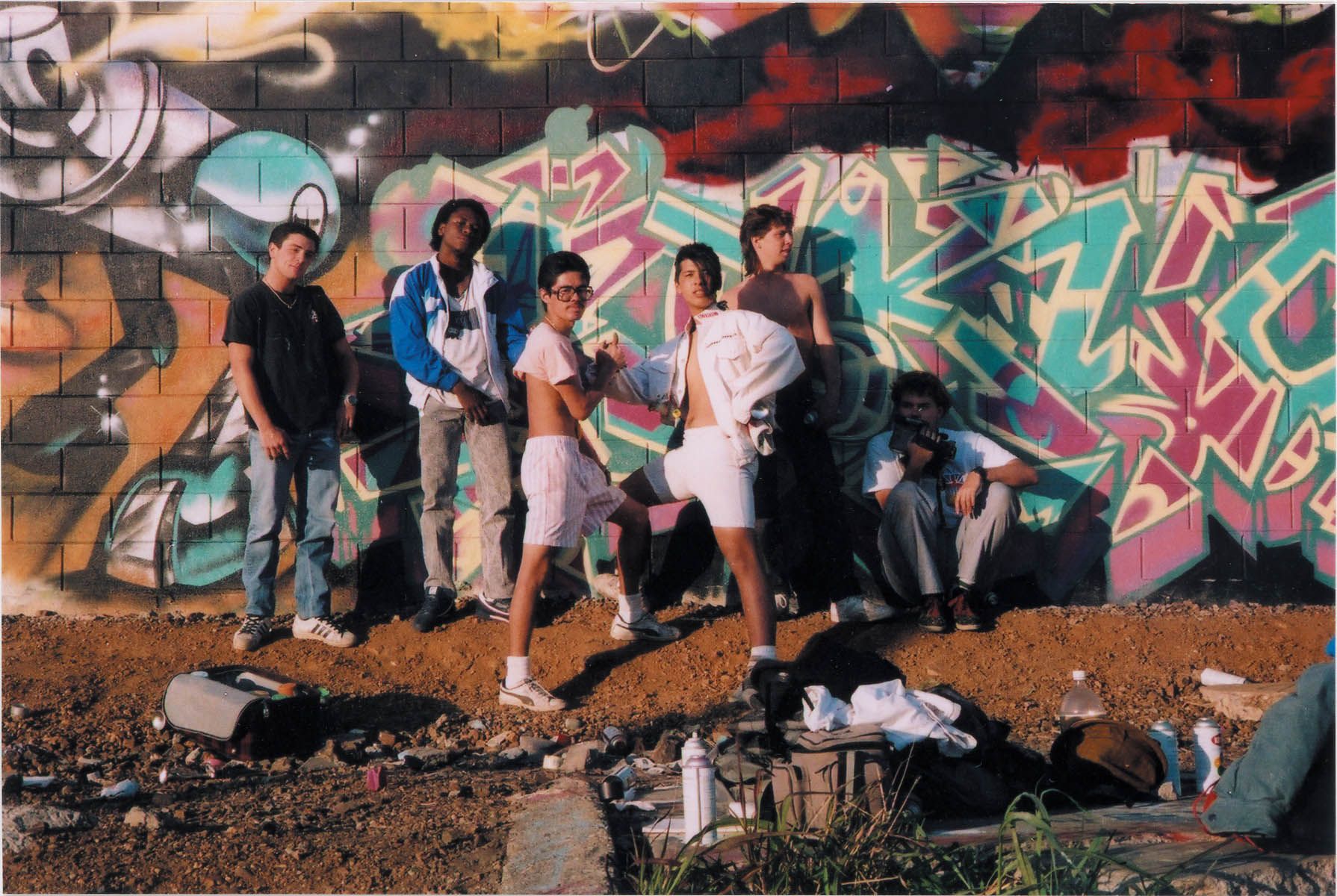

The Aerosolics Tour at the 23rd Yards, 1988.

In this photo: Deen, Ink, Charlie, Slick, Risk, and Power. Courtesy of SPIE

This fall I will be part of the inaugural faculty team for Rennie Harris University. I’ve been invited to share the rich and layered history and legacy of graffiti art in this country with a cohort of students. We owe so much to the visual treasure that graffiti writers and documentarians have shared with us over many decades in the Bay Area. For this month’s Blog, I honor the life and legacy of Mike DREAM (August 15, 1969- February 17, 2000) and Jim Prigoff (October 29, 1927 – April 21, 2021) by sharing an excerpt from my doctoral dissertation about the 23rd yards in Oakland.

Style Wars

The release of Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant’s film Style Wars (1983) had a profound effect on graffiti culture across the globe. The film was shown in Britain and on public broadcasting affiliates across the U.S., exposing the underground culture in New York City to audiences around the world. Most of the writers I interviewed who are old enough to remember the national broadcast of this film credit this it as a turning point, an inspirational movement that propelled them into being prolific graffiti writers.

In the late 1970s, Chalfant began to photograph the graffiti that he saw on passing trains in Manhattan before he ever met any of the writers. Filming began in 1981, and the producers saw it as a way to illuminate the standoff between the local Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and the young teenagers who were painting the trains. They could have never guessed that young people in cities all over would take the film as an official document of the culture and use it as a basis to create their own crews and painting techniques.

In 1987, when James Prigoff and Chalfant included Oakland in their celebrated book, Spraycan Art, it put the city on the map for graffiti writers. The book was recognized internationally and introduced new styles to writers around the world. The Bay Area opening was held at the Mission Cultural Center in San Francisco on September 20th. Most of the images in the book were captured in 1985 and 1986. The Bay Area section has a spread featuring PHRESH and CRAYONE. PHRESH is standing in front of a piece that says, “Stop in the name of Crime.” ESTRIA describes the impact the book had on graffiti culture:

It was the first time that a publication drew attention to the uniqueness of each city. That was the whole point of that book, and that definitely flipped people out, like, “Oh, look what they’re doing here. Look what they’re doing there.” So it opened up your mind to, like, stylistically, “We can try this. We’re not stuck on this one way.” It really opened your mind. And I didn’t really realize how impactful that book was until years later when I look back at how the Internet and the magazines impacted the graff culture.

Oakland Style

In the 1970s and early 1980s before there were graffiti magazines and the Internet, the dissemination of local styles from around the country was dependent on the flics (photographs) that writers would take and circulate amongst themselves. Local styles were stronger and more insulated. Each writer’s personal style usually reflected the region or city that they lived in.

Oakland was known for its funk style, a style that originated with the New York City writers. Like funk music, the general style comes from a grittier, working-class culture. A certain logic exists in funk letters that can be seen in the connection of lines and the form of the letters. Unlike the harder and more angular shapes of other graffiti styles, the funk style lines are rounder and softer. REFA offered his own description of funk lettering:

Funk style is basically the primary style that was coming out of New York City, and it usually consists of what is called “bar letters,” and so it’s a traditional New York style coming out, I would say, between 1977 and 1985, in that time span…. Basic funk or straight funk is more legible, but funk can also be wild too. These days pretty much writers that started writing 1990 and after really don’t know the history about what it is. They don’t even know why they call it funk or what it’s all about. Most of them just don’t, and they’re given a lot of wrong information about the culture and what’s good and what’s not good.

While Oakland’s style is based in funk, it has developed its own unique style. MEUT describes the process as a reclamation of knowledge:

Oakland’s style is really unique in that it’s influenced by New York subway graffiti, and then we kind of took it we made it our own. It’s akin to what people do with knowledge. You read a book, you read a theory, you understand it, and then you become something else. It’s like … with the Panthers, they read theory. You know, they read about people’s struggles. They learned a lot. And then they created the Black Panthers. It’s something that’s really influenced by geography and by, you know, your environments. And that’s what Oakland graffiti has become.

The writers in this study named the crews TDK, BSK, and the Hit Squad as the guardians of Oakland style. They all insisted that style was as the most important element in graffiti writing. ESTRIA explained,

The thing that’s unique about my generation and the New York original schools of writers was that originality was the key point, not, you know, emulating someone else’s style. And so I think because of the Internet and the magazines, it makes it harder for the kids to be more original ‘cause there’s so many styles that have already been developed over, what, the last thirty, twenty-some– thirty years of graff, they don’t even know where to make up something, but whereas for us since we couldn’t see shit, the only resource you had was in your head or what you could see the next guy drawing, so it was all about creativity. So that’s why there were so many different styles coming up.

The 23rd Yards: Where It All Began

With this national momentum, the Bay Area and East Oakland started their own scene. In the early 1980s, writers convened at the train yards where 23rd Avenue dead-ends at the railroad tracks. This half-mile stretch of land was an underground spot where writers could come paint all day without being harassed by the police. In fact, even police officers would sometimes ask if they could try painting with the aerosol cans on the wall. The officers understood that these young writers weren’t violent and that painting was keeping them off the streets. The idea of a free gallery for people to come visit sustained the proliferation of pieces in these yards. Graffiti artists from other cities would hear of the famed yards and travel to leave their marks on the walls.

There was a social aspect of this meeting place: Writers visited and knew that they could find others who appreciated elaborate pieces and emerging styles. SPIE, a San Francisco king, would frequently make the trip across the Bay to visit these yards and his fellow writers. He described the physical parameters of the space:

You come out there, and it’s just like a big, open, wide, another world. You walk for a long while, and there’s lots of rocks, and the place is just covered with graf…. It was blocks and blocks and blocks. Like, you could spot somebody hundreds of yards away, and if you found a spot on the wall that you were just gonna paint, it’s almost like you didn’t even bother to walk down there. It was just like, “Okay, he’s doing his thing, he’s probably gonna be down there for a couple hours. Let’s just start doin’ ours, and then we’ll meet when he’s finished or when we’re finished.”

Southern Pacific once owned these train yards, but after a corporate merger in 1996, it became Union Pacific property. The industrial buildings along the train tracks are viewed by both Amtrak riders and BART passengers, which increases their value among writers. Writers over the age of thirty-five remember the height of activity here. KUFU shared his love for these yards:

Twenty-third has an energy that will forever be within my heart, it will forever be within me. I always will go to 23rd…. It’s like the smell of the train tracks, the smell of the fucking rocks, the sound when you’re walking on them, the sound of BART in the background, the Mexican music playing, the smell of the taco truck, the bums walking around looking at cans, getting drunk at nighttime with dope fiends coughing…. It’s, in fact, a spiritual place for me. I go there and no matter what, that shit is always a serene environment. For other people it’s like, “That shit is crazy, let’s get out of here!” For me, I could sleep there. Literally. I could sleep there. That shit is so comfortable…. It’s like, for me, going into the yard is a ritual experience. Standing in certain parts of the yard is like, “Oh, shit! I remember when such and such was here painting. I remember when we did this, and I remember when I saw that.” It always holds a place in my heart where those are the spots where I’m always going to go.

Access is gained to the tracks from a dead end street under the Interstate 880 freeway, next to the Oakland Housing Authority and the Alameda County Sheriff’s Department Contracting Services Unit. The neighborhood bordering the west side of the tracks from 23rd Avenue to Fruitvale Avenue is called Jingletown. A rumor accredits this name to the cotton mill workers of the first half of the twentieth century who kept their coins in their pockets rather than deposit the money in a bank. Some say that jingling the money in their pockets was a way to show off their earnings on payday while others attribute the behavior to a general distrust of banks (Mailman 2005:130). Jingletown was one of the most ethnically diverse sections of Oakland and today remains a multi-ethnic working-class neighborhood.

Layers of peeling paint create a kaleidoscope of colors that have coated the surfaces of these walls for the past quarter century. The physical surroundings of the yards are bleakly industrial, and loading activity on the docks happens only periodically. Several homeless encampments cluster along the railroad tracks. In this overwhelmingly desolate environment, the walls seem to continue infinitely.

DIME is not old enough to have witnessed these yards in their heyday. She speaks about them with intrigue and wonder:

Sometimes I think, ”Damn, I wonder how many people have been painting in here for many years,” you know what I’m saying? How many years over and over, how many layers of paint, people just from all over have came here to paint, how did everything start?

DIME understands that the history to these walls reaches beyond her years. In the late 1990s, the Department of Public Works began buffing out, or painting over, the walls at the 23rd Yards. Initially, the white walls seemed like an invitation to paint more pieces until one day a huge set of letters reading “DPW” was sprayed on the wall. Today, the 23rd Yards are barely active, only a vestige of a more colorful past. There are a few productions still running from the past few years, but nothing that rivals the activity of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Nevertheless, the stretch of painted buildings remain an unofficial landmark of the city, a sprawling monument that is etched into the minds of many Oakland natives.

The Golden Era

“The Golden Era” of graffiti in the Bay Area coincided with what is commonly understood as “The Golden Era of Hip-Hop” in the 1980s and early 1990s. Corporate America did not yet have the upper hand in controlling and distributing the music that went out to the public. Hip-hop music and graffiti art retained their local flavors because they were not being marketed to the masses in the way they are today. A sense of camaraderie existed amongst all elements of hip-hop artists: breakdancers, emcees, graffiti artists, and deejays. Some of the culture was still being disseminated underground by word of mouth and personal relationships. Hip-hop music took the lead as the leader of the movement. Chang described the way that hip-hop aligned itself with certain political ideologies during this period:

Rappers were increasingly being recognized as “the voices of their generation.” The center of the rap world swung in a Black nationalist direction. Hip-hop culture realigned itself and imagined its roots, representing itself now as a rap thing, a serious thing, a Black thing.” (Chang 2005:231)

The Internet had not yet become a homogenizing force within the culture. Individual writers and graffiti crews shared a camaraderie. There was space at the 23rd Yards to sit and watch others paint that made it an important place where styles were created and disseminated.

The 23rd Yards were a learning community where you could talk to other writers, ask questions, and see styles develop. Between 1982 and 1996, the Oakland Yards were the ultimate location to witness eminent styles and meet some of the most famous graffiti kings. There were opportunities for tutelage and mentorship from some of the best writers in the Bay. In an interview, SPIE revealed the interpersonal aspect of the early years. He describes an exciting creative period where artistic innovation and mentorship were dominant aspects of the culture and illustrates why this time is thought of as “The Golden Era”:

We had 23rd and some other yards to actually go to and feel safe to paint at without getting harassed by authorities or really getting harassed by just folks trying to jack people for their paint or whatever. There was more of a social, kind of, going where people appreciated and respected people putting in work a little bit more. People weren’t out to get each other. And so, being that there was a place to congregate, a lot of people got to meet, and although it might have just been acquaintances, they meant a lot. A lot of them—and because of that a lot of styles were transpassed, and there was a place to actually sit and watch another person paint and just learn some game off of that. So that interaction was that Golden Age, where things were still very pure and things were like … styles were being formed right before your eyes, and you can learn firsthand. You can talk to people. This is an age when Internet wasn’t around. Magazines were very few. Books were very few. And it was a very social, kind of growth element there.

The Aerosolics Tour in 1987 brought writers from Los Angeles to the 23rd Yards. Oakland writers felt honored to be acknowledged by writers who came from out of town to paint with them on their home turf. SPIE recalled the event:

The big thing was when L.A. came up. This was in ’87, and it was like a big deal because when somebody new came from outta town, it was very special. Everybody was very home-grown, bred, and everybody had their hometown heroes, but when you had someone come from outta town it was just like, you felt like you were living in an area that was being specially recognized from people very far away. If they had enough energy to come out and spend time and do something in your ‘hood, then it was like, “Whoa. Boy, I feel pretty special.” So, when L.A. came up for the the Aerosolics Tour– It was RISKY, SLICK, DREAM [FROM L.A.], SMD from L.A., Charlie…. When they came up, it was like, Dream, Dream’s partner Joe Red, and a whole bunch of other folks, they came out with a barbecue, they brought a whole pit out there, to the 23rd tracks, and just barbecued the whole time. [We] had a [boom]box out there. [There was] TMF, DEEN, and INK. There’s photographs. CRAYONE was out there, too, and of course ESTRIA and his brother BAM, so it was like a TWS collaboration … it was just like folks really wanted to make a good welcoming to this L.A. crew. And when they came up, it propelled the Bay Area to a whole different new era, because when they came up they started using the phantom caps.

Phantom caps are a special tip for aerosol cans that create very thin lines, and this advancement changed writing in the Bay forever. It allowed writers to innovate styles and create lines they would have never imagined possible before. It also made Oakland an official graffiti city, recognized by writers from afar.

Postscript

In fall 1993 two graffiti artists, NUKE and DUKE, delivered a lecture to a class on public art taught by UCLA professor and Chicana muralist Judith Baca. The class was a public art course in the World Arts and Cultures Department at UCLA. Their lecture addressed the ephemeral nature of graffiti, its ability to deter youth from gang life, and the development of the practice as an art form over time. Students had an opportunity to watch a video that featured graffiti writers and graffiti opponents, then ask questions of the two veteran painters. The Los Angeles Times ran a story about the class and, a week later, published several scathing letters to the editor. In a letter published on November 25, 1993, David Pabian of Los Angeles wrote:

It’s invigorating to see that irresponsible social sentimentality is alive and well at UCLA in the person of visiting instructor Judith Baca, whose stated aim in having two graffiti vandals lecture her class was to explore the “fine line between community sensitivity and censorship.” I suggest the only “fine line” to be drawn where Baca is concerned is the one across her name on the UCLA payroll.

What side is she on, sensitivity’s or censorship’s, where freeway signs made illegible by childish scrawls are concerned? Is she aware of the tremendous costs, public and private, of removing this stuff?

I’d say I’d like to see her home get covered with the puerile spray paint scribbles of these infantile ego strutters, but she’d probably find [it] a “vital and life-affirming statement.” And besides, her blighted neighbors would then be forced to either struggle with that fine line between community sensitivity and censorship themselves, or just throw in the towel yet again and become just a little bit more demoralized.

The scornful sentiment expressed in this letter was echoed in all of the editorials about Baca’s class that day. UCLA was attacked, Baca was belittled, and the two graffiti writers were called “jerks” and criminals. In his letter, Pabian suggests that Baca would change her tune if her own home was vandalized, an argument that is commonly brandished by anti-graffiti activists.

Over a decade later, after starting the data collection for my dissertation in the same department where NUKE and DUKE had delivered their lecture, the academic community confronted me with the same question. After describing my project to a sociology professor from Cal State Northridge, he asked me a favor. He said, “Once you get your participants in a room for an interview, ask them this question for me: How would they like it if someone drew on their home?”

This request indicated to me that the graffiti writers he was imagining were not the same as the writers in my study. In fact, the graffiti artists in my study have deliberately refused to write on a person’s home as a matter of principle. While the question seemed trite to me at first, I took the time to think about each my participants and their personal relationships to private property and community responsibility.

I tried to picture what it would be like to ask a Native American how he would feel if his home was written on. It seemed that this trespass would pale in comparison to the centuries of genocide inflicted on the indigenous populations of this continent. I tried to fathom what would happen if I asked a Cambodian refugee who was relocated to unlivable housing conditions in an Oakland ghetto, how he would feel if someone wrote on his house. While I was not sure what exactly the response would be, the questions didn’t seem fitting. I knew my research questions needed to probe deeper…